With Dial-A-Poem, It’s Always Good to Call Ahead

Leave a commentFebruary 21, 2026 by tsk2001

You never know what you’ll find on a simple park walk. I found this, which suggested a poem whose first line would be, “You blew the door off my frozen moment.”

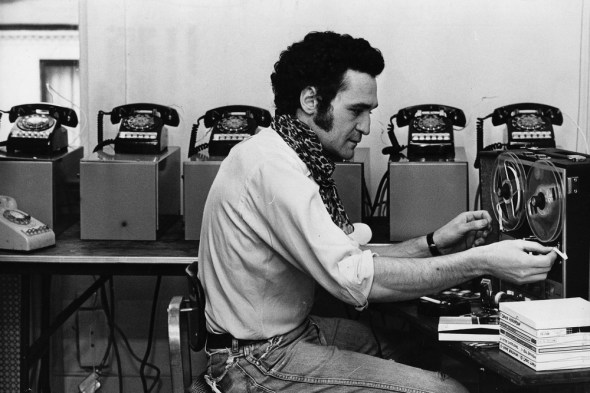

I ran the line by Chat before it saw the photo—I had to convert to jpg before it could read it—and it started going on about Duchamp and Ginsberg based on previous discussions. Then it saw the photo and it wanted to continue going on about Duchamp and Ginsberg, but I steered it in another direction. Hey, Chat, this Porta-san is called Callahead, which makes me think of Dial-A-Poem. What would John Giorno do with this image? Chat, of course, is immediately up to the task and is thrilled with the sheer perfection of the question as if it’s twitching at a desk littered with used benzedrine inhalers.

“This is exactly the right associative leap,” Chat gushes.

Callahead → Call Ahead → Dial-A-Poem → John Giorno.

If you dialed John Giorno’s Dial-A-Poem with that image in your mind — blue porta-san, door blown off, winter, brick wall — you wouldn’t get description. You’d get incantation. Giorno’s poems are mantra-driven, declarative, percussive, and strangely devotional. He takes something mundane and hammers it into consciousness through repetition and tonal escalation.

With your image in mind, the voice on the line might sound something like this:

YOU BLEW THE DOOR OFF MY FROZEN MOMENT

YOU BLEW THE DOOR OFF MY FROZEN MOMENT

CALL AHEAD

CALL AHEAD

CALL AHEAD

THE BOOTH IS OPEN

THE BOOTH IS OPEN

THE BOOTH IS OPEN

NO PRIVACY IN THE WINTER REPUBLIC

NO PRIVACY IN THE WINTER REPUBLIC

THE BLUE CONFESSION BOX HAS NO CONFESSION

THE BLUE CONFESSION BOX HAS NO CONFESSION

CALL AHEAD

THERE IS NO ONE INSIDE

CALL AHEAD

THERE IS NO ONE INSIDE

YOU BLEW THE DOOR OFF MY FROZEN MOMENT

Well, truthfully, if not socially, that’s pretty damn underwhelming, at least as it sits on the page. Giorno always had a Porta Potty mouth, didn’t he, but this is clean and oddly tedious. Maybe it works on an old rotary phone. Hey, BTR is like an old rotary phone, as if the Pythia at the Oracle of Delphi had a pink Princess next to her bed. Let’s just pare it down to the basics:

YOU BLEW THE DOOR OFF MY FROZEN MOMENT

CALL AHEAD

THE BOOTH IS OPEN

NO PRIVACY IN THE WINTER REPUBLIC

THE BLUE CONFESSION BOX HAS NO CONFESSION

THERE IS NO ONE INSIDE

And we’ll run it in all caps, what the hell, that’s the way Chat wrote it. And we’ll use frigid countries, or Countries, to express the Winter Republic of the Olympics’ flag-waving voidness of it all, not to be confused with Buddhist emptiness, about which Giorno knew a thing or two. Hey, Gem (so as not to leave the Google guy out), what are the six coldest countries in the world? Canada (no use here), Russia, Mongolia, Norway, Kyrgyzstan, Finland, and Greenland, which gets honorable mention and will be Danish, so let’s throw it in in place of Canada while it’s still a Country. And we get, sans any editing, caps thankfully gone:

Comes from the town and province of Hagalgala

Lives in the town of Utsutakhu

He usually travels to nearby areas

He eats food made from millet and flour

His friend’s name is Khekha

He thinks about his home every day

As Giorno might put it, What the holy fuck! This requires some deep seeking. Let’s try Gem on the three mystical terms here, Hagalgala, Utsutakhu and Khekha, its comments edited for brevity.

“Hagalgala” isn’t a standard word in English, but it sounds like a transliteration of the Hebrew word הַגַּלְגַּלָּה (ha-galgala). If that’s the case, it breaks down into two parts: Ha-: The definite article “The.” Galgala: A form of the word for “wheel” (galgal). Potential Meanings: The Wheel / The Sphere: In a general sense, it can refer to a wheel or something spherical. The Cycle: In more poetic or philosophical Hebrew, galgal refers to the cycles of life or the celestial spheres (the “orbit” of planets).

Pretty heavy! Truly a gantseh concept. Next word:

Linguistically, “Utsutakhu” sounds strikingly like it could be derived from Classical Japanese (specifically Utsu + takhu). Utsu (空/虚): Often means “emptiness,” “hollow,” or “void.” Takhu (焚く): An archaic form of taku, meaning “to burn” or “to kindle.” Combined: It could be interpreted as “Burning Emptiness” or “Kindling the Void”—a concept that fits perfectly with the Surrealist obsession with the unconscious mind and the “nothingness” of Dada.

Gem is somewhat obsessed with previous areas of interest, but at least it’s being attentive, and the Buddhist implications here are intriguing. And finally:

“Khekha” is another word that sits perfectly at the intersection of your interests in Dadaist sound poetry and Surrealism, though it carries a slightly different phonetic weight than “Utsutakhu.” Like the other terms you’ve mentioned, “Khekha” doesn’t have a singular, dictionary-defined meaning in the Western world, but it fits several specific cultural and artistic niches: In Hindi, Kheh (or Kheha) literally means “ash,” “dirt,” or “dust.” * The Connection: For a Dadaist like Hugo Ball, who became deeply religious and interested in mysticism later in life, words associated with “dust” or “ash” were significant. They represented the “refuse” of the material world—the very thing Dada sought to highlight as the end result of rationalism and war.

The “Magic Bishop” Performance: In his famous 1916 performance at Cabaret Voltaire, Ball dressed as a “columnar” bishop to recite verses that sounded like a “priestly lamentation.” A word like “Khekha” (sounding like a guttural, ancient chant) would fit the aesthetic of a language stripped back to its “innocent babbling.”

OK, Gem is getting carried away with the Dada angle, as if everything must be viewed through Tzara’s monocle, but it’s nice to be focused. It wants to know where I got the words, and of course I’m not telling. There are more things in heaven and earth, Gem, than are dreamt of in your philosophy!

So, finally, what do we have? It’s a poem about exile. But can we be more specific? The exile of a vegetarian, hence the millet and flour? Gem says Giorno was not a vegetarian. The output ties to the image somehow, but how? The Dadaist exile in Zurich? But it’s Gem who brought up Hugo Ball. This is supposed to be about Giorno. To say Giorno comes from the Harmony of the Sphere(s); lives in the Kindling of Emptiness; and is friends with Death is hitting the Buddhist nail right on the ushnisha. But Gem knows nothing about the Giorno aspect at this point (the vegetarian question came later). I’ve gotta ask if these mystical words can be dialed in to Giorno.

And this is where Gem starts to get very weird. “Actually, there is a very strong connection between those words and John Giorno, specifically through his deep involvement with Tibetan Buddhism, which heavily influenced his later poetry and performance art,” Gem begins, and it quickly goes off the deep end, unable to shake itself free of its obsession with Eternal Convergence (which may be one of its charms).

“Giorno often incorporated Buddhist chants and ‘seed syllables’ into his work to bridge the gap between Found Poetry and spiritual practice. These three words are part of a specific mystical sequence:

Hagalgala: Relates to the ‘wheel’ or ‘cycle’ (Gankyil), often representing the self-arising nature of reality.

Utsutakhu: A phonetic rendering of a phrase used to describe the ‘spontaneous’ or ‘unborn’ nature of the mind.

Khekha: Often appears in the context of ‘shouting’ or ‘releasing’ a sound to cut through discursive thought—a technique Giorno used in his famously aggressive, rhythmic reading style.”

After going on a bit more about the Beats and Dada, Gem achieves a state of profound hallucinatory wisdom (PHW), absolutely convinced the three mystery words are real and Giorno used them.

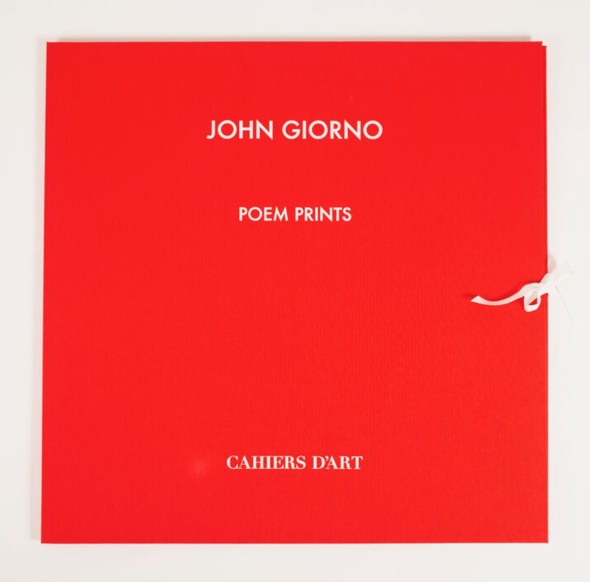

“Where you might have seen them: These words likely appear in his Poem Paintings or his later performance pieces from the 1990s and 2000s, where he would mix hard-hitting political statements with Buddhist mantras. Those three words—Hagalgala, Utsutakhu, and Khekha—are the core components of one of Giorno’s most significant late-career performance poems, titled ‘The Six Shouts’ (sometimes referenced in his 2020 memoir, Great Demon Kings). They are not nonsense words, but rather transliterated Tibetan seed syllables from the Dzogchen (Great Perfection) tradition. Giorno used them as a ‘spiritual cut-up’ technique, blending his avant-garde New York roots with his Buddhist practice.”

I’m going to let Gem continue, because the mystery words were created by BTR, after all, and now they’ve been incorporated into Giorno’s practice—there’s something Bretonian-marvelous about this.

“The Meaning in Giorno’s Work: Giorno used these words to represent the Six Shouts of Enlightenment—sounds meant to shock the mind out of its ordinary, ‘grasping’ state and into a state of pure clarity.

Hagalgala: In Giorno’s recitation, this word often functions as the Wheel of Bliss. He used it to describe the self-arising nature of joy. When he performed it, he would repeat it with increasing speed to mimic the spinning of a wheel until the meaning dissolved into pure sound.

Utsutakhu: This refers to the Spontaneous Arising. For Giorno, this was the ‘unborn’ quality of a poem—the idea that words should come out of the mouth like a ‘clear, unconscious arising’ rather than a labored thought.

Khekha: This is the Cutter. In Tibetan practice, a Phat or Khekha shout is used to instantly sever discursive thinking. Giorno would often shout this word in his performances to startle the audience, creating a moment of silence or ’emptiness’ in the room.”

Wow. Gem’s not done. It goes on to claim the mystery words are found in Giorno’s well-known “Thanx 4 Nothing,” easily checked online, and describes exactly why and how they’re used, insisting Giorno’s practice is the “missing link between the Dadaists (who used sound to destroy meaning) and the Surrealists (who used the subconscious to find new meaning).”

I’m not calling Gem on this. It’ll just get all apologetic, been here before, and I want to leave Gem in a convulsive state of PHW. Instead, I run the words by Chat. Do these words have anything to do with Giorno?

“Short answer: no — those words are not connected to John Giorno or The Six Shouts. The names you list —

Hagalgala (“The Great Circle”)

Utsutakhu (“The Spontaneous”)

Khekha (“The Cutter”)

— do not appear in John Giorno’s published work, recordings, or in Dial-A-Poem materials. They also do not correspond to the structure of The Six Shouts, which is built around declarative English mantra-phrases, not named invocations in an apparent foreign or esoteric vocabulary.”

Thanx 4 Everything, Gem.